updated 17 July 2017

in all the talk about hard/soft/clean/full/transitional Brexit, there is a dangerous assumption that it is a solution to problems the UK faces.

it is in fact a huge distraction from what government really needs be concerned about: a growing crisis in housing supply, the NHS, social care, education and the Prison Service, to name just the most obvious. none of these will be solved by reducing the country’s financial contributions to the EU; nor by restricting free movement of people more than EU treaties already allow; nor by removing the country from the jurisdiction of the European Court of Justice.

the ills of this country lie squarely at the door of our own government.

an abuse of democracy

the value in democracy is not that it elects good governments; it is that it provides a civilised mechanism (as opposed to a military coup d’état) for removing bad governments. in the absence of a credible opposition ready to take over, a bad government remains in power. bad government is better than no government.

the Brexit referendum was an abuse of democracy: it allowed people to reject membership of the EU, but neglected to offer a viable alternative (the equivalent of a new government).

if the US election had been held in the style of this referendum, it would have asked the people, “would you like Barack Obama to remain or leave the Whitehouse?” it is then as if a working group of Congress decided that Trump should be the new president, claiming the popular vote mandated support for Trump.

we voted for a negative, a vacuum into which politicians could pour their fears and fantasies.

the referendum did not bind MPs to any particular course of action. no MP should have felt mandated to support invocation of Article 50 unless and until he or she believed that the consequences will be in the best interests of the country, their constituents and future generations. blind faith in a positive outcome is an abrogation of responsibility.

blame the EU

the EU has become the object of blame for a whole range of UK government failures – and not just by the Cameron/Osborne government, but more seriously by the Blair/Brown governments. the latter accepted immigration to the UK (on a scale even greater than they forecast) because it generated economic growth. migrants from Poland suited Britain well, providing productive workers for the building trades and arable farming in particular. our health service has long depended heavily on immigrants from the EU (as well as India and the Philippines).

but Blair, Brown, Darling, Cameron and Osborne all missed one stunningly obvious (with hindsight maybe) point: net immigration means a greater demand on housing, transport, education and health. when Labour under Blair was elected in 1997, the country was already severely underinvested in transport infrastructure, health and education. in its first term in government, it took steps to remedy those, but neglected housing until 2003.

immigration took off almost immediately after Labour was elected, initially from non-EU countries, but the accession of Eastern European countries to the EU shifted the balance. Labour governments took the bonus of increased tax revenue resulting from economic growth and banked it (running budget surpluses from 1998 to 2001).

the UK backed expansion of the EU in 2004, and opted to impose few restrictions on immigration from acceding countries, unlike, for instance, Germany and France. it also backed expansion in 2007 (but this time imposed restrictions for seven years, as permitted by the accession agreements).

EU citizens who are non-economically active (studying, retired or unemployed) their right to reside in the UK “depends on their having sufficient resources not to become a burden on the host Member State’s social assistance system, and having sickness insurance.” the UK does not publish figures for numbers of EU citizens deported under this requirement, but the number is thought to be low. (it is likely that other countries have been simarlarly lenient on non-economically active UK citizens residing in their countries.)

after the banking crash in 2008, government investment was diverted towards bailing out banks and fire-fighting an economy in recession – and on the edge of depression. investment in housing, health, education and other local government services all took a back seat. but net immigration was still high and rising, so demands on housing, health, education and other local government services also continued to rise.

it was inevitable that people would cry foul. they voted Labour out in 2010, but the Conservatives offered no respite. in fact they tightened the screws and meddled with, without fixing, the NHS and education. they did however start to address the burgeoning housing crisis, controversially by relaxing planning regulations and offering financial assistance to first-time buyers. but the acceleration in house building was much too slow to catch up with demand.

the vote for Brexit was a natural and (in hindsight) predictable outcome of years of underinvestment by successive governments in housing, transport infrastructure, education, health, social care and other local government services. UKIP and the larger part of Labour and the Conservatives all scapegoated the EU rather than admit that the blame lay with UK governments.

it is therefore no wonder that the other 27 nations of the EU feel little sympathy with the UK. we have reaped benefits of EU membership, and now we are blaming the EU for our own governments’ mismanagement.

it might also be added that the refugee crisis faced by continental Europe is a direct consequence of military actions that the UK advocated and pursued independently of the EU, including invading Iraq, bombing Libya, and intervening covertly in Syria.

no way back

once Article 50 is invoked, the UK is committed to leaving the EU within two years. the law (British or EU) might provide a let-out; the other member states might allow us to change our mind. but, for now at least, exercising that option would lead to civil war (at least in the media, if not on the streets). if there is one point on which everybody can agree, it is that the referendum was a vote to leave the EU.

a proportion of those who voted Brexit believe that the EU is a bloated bureaucracy that we can do better without. probably most people would agree with the first part of this assertion. the real point of disagreement is over the consequences of Brexit, which are unprovable. hence no argument is likely to change the mind of a principled or optimistic Brexiteer.

a larger proportion of those who voted Brexit believe that leaving the EU will reduce pressure in the UK on housing, employment, health, education and other local government services. it may do in the short term, but the loss of labour will quickly result in a crisis in the construction industry, farming, health and social care, academia, and other parts of the UK economy. there will inevitably be a loss of tax revenue, from a smaller population and slower growth. this will put even greater strain on central and local government finances at a time when the population’s needs (especially for social care) and expectations (especially for health care) are rising. (see the ‘low migration’ scenario produced by the Office of Budget Responsibility.)

the brain drain

perhaps less discussed is the likelihood of a ‘brain drain’ of academic researchers. universities have become highly productive engines for the economy, spinning out start-ups to exploit new discoveries and inventions. the loss of foreign postgraduate researchers, and more attractive opportunities for British academics to work abroad will lead to a reduction in entrepreneurial activity in the UK.

the UK government may wish to offer sweeteners to companies to remain in the UK, for instance by lowering corporation tax. but that will disincline EU or EEA member countries from agreeing to grant privileges to UK companies, such as ‘passporting’, as part of a future trade deal. the Netherlands has already made this point.

without incentives and facing years of uncertainty, major banks, car manufacturers and other multinationals may choose to minimise risk by relocating their headquarters, R&D, manufacturing and service centres away from the UK. the consequences for the UK economy and future competitiveness could be dire.

is there an alternative to Brexit?

if there is an alternative to Brexit, it is not a legal loophole that annuls or blocks the referendum. nor is it a vote in Parliament to reject the Brexit agreement (which, in all probability, would mean that the UK drops out of the EU without an agreement).

it would need to be a credible commitment by government to embark immediately on a massive programme of investment in housing, transport, health, energy, policing, education, social care and other local government services. but that will be needed even if we leave the EU – possibly even more so.

investment on the scale required will entail increasing taxes and/or government borrowing.

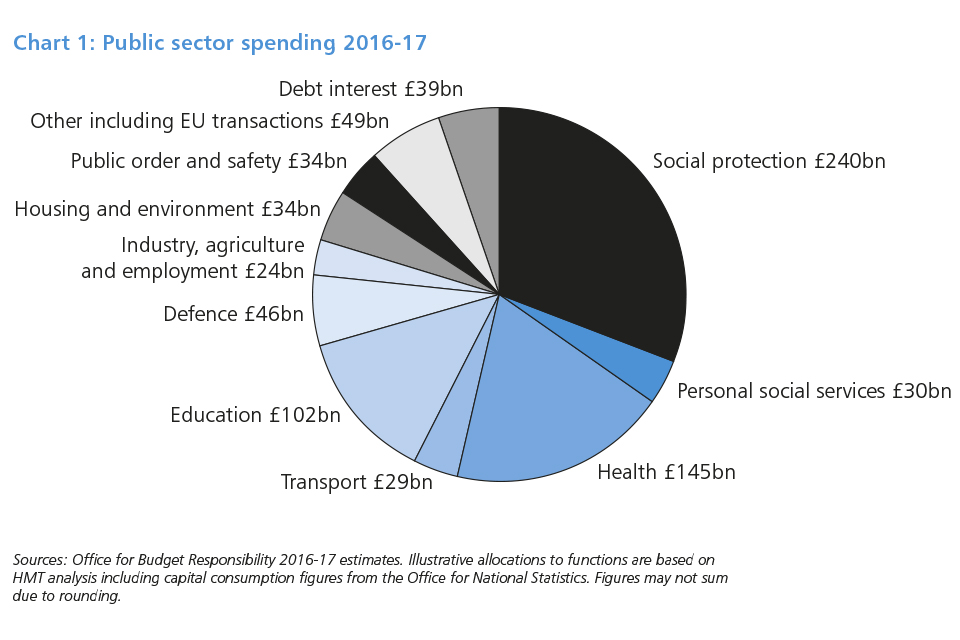

the national debt already costs £39bn/year, four times the UK’s net contribution to the EU budget. that cost will rise significantly if the UK government is seen to become a riskier borrower. long-term gilts currently trade at around a 2% return. an increase of a fraction of a percentage point would make new and renewed debt considerably more expensive.

there is little appetite to raise income taxes (including National Insurance), sales taxes (VAT and duties) or corporation tax. so government will need to be more creative about tax-raising opportunities: for instance, on multinational corporate earnings, land, intellectual property, financial transactions, commodities, CO2 emissions, pollutants, and infrastructure usage (including roads and airports).

local governments are losing the Revenue Support Grant from central government, but are constrained to raising Council Tax by under 2% without a referendum. there are more efficiencies yet to be gained, e.g. through greater collaboration between local governments and other agencies, and better use of technology; but these savings will take many years to realise, and require considerable up-front investment of money and expertise. most savings are now being found by cutting or reducing access to services, such as social care, public transport and legal aid, which poorer people depend on.

conclusion

the law does not provide a let-out from politics. if the UK government does not offer a radical alternative to Brexit, then Brexit is inevitable (as most now believe it is anyway). but Brexit is not a solution.

Brexit creates huge new challenges, for which the civil service is ill-equipped to handle. it is also a huge distraction from the work that government really needs to be doing: reversing a decade of underinvestment in core infrastructure; correcting the mistakes made by previous and current governments; and relieving the financial straightjacket from local government.

MPs must take their responsibility to future generations as seriously as their responsibility to those who voted to leave the EU. they must use their judgement to interpret the referendum’s meaning, and act with courage.

Leave a Reply